Do you (or your students) study the American Revolution? Would you like to save and receive funds for your research?

In this post you will learn about the David Library of the American Revolution, its research fellowship for graduate students and post-doctoral scholars, and its award for undergraduate research.

Brief Overview: The David Library of the American Revolution

Brief Overview: The David Library of the American Revolution

The David Library of the American Revolution (DLAR) supports and promotes the study of the American revolutionary era ca. 1750-1800.

Businessman, philanthropist, and revolutionary-era enthusiast Sol Feinstone (1888-1980) founded the David Library in 1959; he named the institution after his grandson David Golub. Feinstone began the DLAR with his extensive, private collection of revolutionary-era manuscripts. In 1974, he built the present library and auxiliary buildings on his 118-acre farm in historic Washington Crossing, Pennsylvania and opened them to the public.

5 Reasons Why You Should Research at the David Library

Below I provide my top 5 reasons for why you should study at the David Library of the American Revolution.

The first 3 apply to anyone who researches the American Revolution. Reasons 4 & 5 discuss two perks of being a DLAR fellow.

1. The Collections

The David Library possesses “all [of] the basic primary sources” on the American Revolution and its War for Independence.

The David Library possesses “all [of] the basic primary sources” on the American Revolution and its War for Independence.

The Library also holds records that speak to the French and Indian War and the early republic United States.

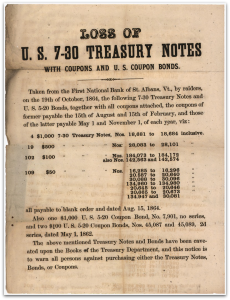

The DLAR has acquired materials from around the world; the library has over 10,000 reels of microfilm in its collection.

Rather than undertake expensive and time-consuming travel across the United States, Canada, Great Britain, and France, researchers will find nearly all of the information they seek within the printed, manuscript, and microfilm collections of the David Library.

Don’t believe me? Take a look at their “Guide to Microfilm Holdings.”

2. Knowledgeable Staff

Librarian Katherine A. Ludwig knows the collection.

If you study the American Revolution, you should contact Kathie and spend a few minutes describing your project and the information you seek. Within minutes she will point you toward records and correspondence that you either did not know existed or that you thought you would spend thousands of dollars on overseas travel to find.

3. Scenic and Historic Location

Few archives offer as much complementary, scenic inspiration for their subject matter as the David Library.

Sol Feinstone’s 118-acre farm overlooks the Delaware River near the spot where George Washington crossed for his surprise attack at Trenton and Princeton, New Jersey on December 25/26, 1776.

Whenever you need to peel your dry, tired eyes from the books and microfilm you have spent all day reading, you can take a walk around the farm or along the Delaware River to recharge your spirit, mind, and eyes.

4. Fellows Get 24/7 Access to the Library

Are you a night owl who yearns to research at 3am when your mind is at its best?

The David Library opens for public research Tuesday through Saturday, 10am-5pm. But, if you apply for and receive one of their fantastic fellowships, you will have access to the library and its holdings any day or time you want.

The David Library is always open to its fellows.

5. Housing and the Customizable Social Experience

5. Housing and the Customizable Social Experience

The David Library offers its fellows a room in Sol Feinstone’s farmhouse as part of their fellowship.

Fellows work with Chief Operating Officer Meg McSweeney to schedule their month-long research residency. Upon submitting the dates you would like to work at the David Library, Meg will advise you as to how many other fellows plan to be in residence during the dates you provide. This information will allow you to customize your experience.

Scholars who prefer solitude will be able to select a time when few other scholars will be in residence. Historians who love to work amid the company of other scholars can choose a time when several scholars plan to be in residence.

Doctoral and Post-Doctoral Fellowships

Fellowship Term: 1 Month Award Amount: $1000-$1600 plus housing Who Can Apply: Doctoral Candidates and Post-Doctoral Scholars Due Date: March 7, 2015

The David Library expects to appoint approximately 8 fellows for 2015-2016.

The David Library Academic Advisory Council is an open-minded body that seeks applicants who study history, Africana studies, gender studies, women’s studies, political science, religion, law, geography, or any other area that the DLAR collections support research in.

The David Library Academic Advisory Council is an open-minded body that seeks applicants who study history, Africana studies, gender studies, women’s studies, political science, religion, law, geography, or any other area that the DLAR collections support research in.

Application Materials: Application materials include 6 copies of a research proposal, CV, and writing sample plus 2 letters of recommendation.

Undergraduate Research Fellowship

First Place Award: $500 Second Place Award: $250 Third Place Award: $150 Entry Deadline: June 30, 2015

New for 2015: The David Library of the American Revolution just announced its brand-new Omar Vázquez Prize for Excellence in Undergraduate Research.

Any undergraduate enrolled in an accredited 4-year college or university in the United States may apply for this award. To apply, they must submit a research paper (up to 30 pages) written as a requirement for an American history or Early American Studies course during the 2014-2015 academic year. The paper may cover any area related to early American history circa 1750 to 1800.

The DLAR Academic Advisory Council strongly encourages any student who has made use of DLAR collections to apply.

Application Materials: 1 paper up to 30 pages in length, written in English, and formatted with double spacing, 12 pt. Times New Roman font, and Chicago Manual of Style foot or end notes. Applicants should also include a Works Cited page, which will not count toward the 30-page limit.

Applicants who wish to submit a portion of their undergraduate thesis may do so, but must include a table of contents in addition to all of the above (table of contents will not count toward 30-page limit).

Visit “Omar Vázquez Prize for Excellence in Undergraduate Research” for more details and submission requirements.

Conclusions

Conclusions

In 2008, I had the honor to be a fellow at the David Library of the American Revolution. It was one of my best, and most unique, fellowship experiences.

My trip to the DLAR saved me time and money. Kathie Ludwig helped me access records that I would have had to travel all around the United States, Canada, and Great Britain to read.

My DLAR fellowship also helped me to extend my educational experience beyond my historical research.

Being a rather social person, I opted to visit when many other scholars were in residence. My interactions with these scholars not only helped me network with senior colleagues, but it allowed me to learn from their knowledge and experiences.

All of the other fellows I encountered helped me locate collections that might be helpful to my research. They also shared invaluable information about how they obtained their academic jobs, why they thought they had yet to be successful in their pursuit of a tenure-track position, how they published their first books and articles, and information about other archives that would benefit my research.

The presence of these scholars enriched my mind and relieved my scholar’s solitude— that feeling of loneliness many of us experience when we leave our families for weeks at a time to spend hours with books, manuscripts, and microfilm records.

I enjoyed my fellowship experience at the David Library of the American Revolution immensely.

Note for Independent Scholars

Note for Independent Scholars

I held my fellowship at the David Library as a graduate student, but my experiences with the DLAR, its staff, and previous fellows has left me with the impression that the David Library Academic Advisory Council would welcome and seriously consider applications from independent scholars who hold doctorates.

What Do You Think?

What are your favorite libraries and archives?

Do they offer fellowships for historians?

*Pictures of DLAR Farmhouse & Library building courtesy of the David Library of the American Revolution.