On April 9, 2015, the Massachusetts Historical Society convened “‘So Sudden an Alteration’: The Causes, Course, and Consequences of the American Revolution,” a conference to discuss the present state of scholarship on the American Revolution.

The conference marked the second in a three-part series aimed at reigniting interest and work on the American Revolution. (The first conference, Revolution Reborn, took place in June 2013.)

On April 9, 2015, the Massachusetts Historical Society convened “‘So Sudden an Alteration’: The Causes, Course, and Consequences of the American Revolution,” a conference to discuss the present state of scholarship on the American Revolution.

The conference marked the second in a three-part series aimed at reigniting interest and work on the American Revolution. (The first conference, Revolution Reborn, took place in June 2013.)

Over two and half days, conference-goers attended nine sessions that explored new scholarship centered on the American Revolution. They also listened to two keynote addresses that lamented the state of the field and its lack of “originality.”

In this post, you will discover a recap of some of the new scholarship on the American Revolution, the two keynote addresses, and my take on whether or not the field suffers from an “originality crisis."

New Scholarship

‘So Sudden an Alteration’ offered attendees the opportunity to attend seven of nine sessions that previewed the works-in-progress of approximately twenty-eight historians of the American Revolution.

The sessions included new work on the Stamp Act crisis, the Boston Massacre, slavery, the War for Independence, revolutionary settlements, and the global nature of the Revolution.

Below you will find brief summaries of the work offered at three panels to give you a feel for the scholarship discussed.

Session 1: The Stamp Act

The conference opened with a look at the Stamp Act.

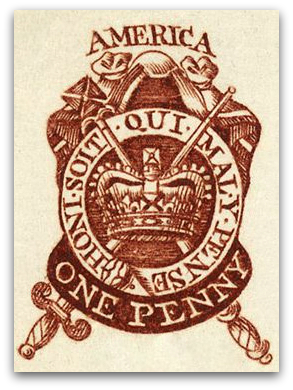

Nancy Siegel explored the imagery of the Stamp Act crisis and the subsequent discord between Great Britain and her thirteen North American colonies. She noted how printmakers employed a satirical mother and daughter motif in their images—printers often portrayed North America as a bare-breasted Native American female warrior— and explored how those images changed over time. Siegel noted that visual satire allowed Britons to express and discuss their views on the imperial crisis as it unfolded.

Nancy Siegel explored the imagery of the Stamp Act crisis and the subsequent discord between Great Britain and her thirteen North American colonies. She noted how printmakers employed a satirical mother and daughter motif in their images—printers often portrayed North America as a bare-breasted Native American female warrior— and explored how those images changed over time. Siegel noted that visual satire allowed Britons to express and discuss their views on the imperial crisis as it unfolded.

Craig Smith examined the Stamp Act from the angle of honor. He argues that the colonists had a strong sense of honor—reputation based on an individual’s proper conduct—and that the passage of the Stamp Act violated it. Parliament challenged the colonists' honor by implying that like deadbeats, the colonists would not contribute to the well being of the empire without legislation. Furthermore, by passing the Stamp Act without their consent, Parliament relegated the colonists to a slave-like status; slaves did not have honor because they lacked both freedom and independence.

Richard D. Brown commented that both papers serve as a “launching point” for a discussion of American identity creation. They also offer interesting examples of how we might use gender and culture as lenses to view the events of the American Revolution.

Session 3: Toward the Revolution

What caused the thirteen British North American colonies to split from Great Britain?

Christopher P. Magra, John G. McCurdy, and David Preston shared their insight by exploring press gangs, the Quartering Act, and the loss of British preferment experienced by British officer-turned-Patriot Charles Lee. Christopher P. Magra seeks to revive the economic origins of the American Revolution with his study of British Naval impressment. Magra argues that scholars have turned away from the economic origins of the American Revolution because they believe that the colonists cared more about how Parliament passed taxes (without their consent) than they did about the economic burdens the taxes imposed. Magra seeks to move the economic origins back near the center of what caused the American Revolution by examining the economic hardships experienced by Rhode Islanders as a result of British naval impressment in 1765.

John G. McCurdy promises to resurrect the Quartering Act. Historians have claimed that the Quartering Act would have allowed the British government to billet soldiers in the colonists’ private homes. McCurdy’s findings reveal that Parliament had no such intentions. They also disclose how historians can use the Quartering Act and the debates surrounding it to see Parliament’s insufficient knowledge of its colonies and the colonists’ developing interest in a right to privacy.

John G. McCurdy promises to resurrect the Quartering Act. Historians have claimed that the Quartering Act would have allowed the British government to billet soldiers in the colonists’ private homes. McCurdy’s findings reveal that Parliament had no such intentions. They also disclose how historians can use the Quartering Act and the debates surrounding it to see Parliament’s insufficient knowledge of its colonies and the colonists’ developing interest in a right to privacy.

David Preston has embarked on a project that explores why the American Revolution did “not disintegrate into endless civil war, political retribution and violence or into a military dictatorship or monarchy, as have many other revolutions in world history.” His paper, “Loyalty and Subjectivity in the Postwar British Empire: The Strange Career of Charles Lee” offers insight into the human dimensions of the American Revolution and War for Independence by investigating how Charles Lee grappled with the questions of loyalty and identity. For Lee, and most Americans, decisions of loyalty and national identity were fraught with emotion, an aspect that historians have often erased because they assume that American independence occurred naturally and inevitably.

Robert A. Gross remarked that impressment, quartering, and Charles Lee's loss of preferment all played a role in why Americans decided to break with Great Britain. He noted that many historians portray the American Revolution as inevitable, but that Magra, McCurdy, and Preston have reintroduced contingency to our understanding of the American Revoltion; the period 1765-1775 did not witness a march to the Revolution, events could have turned out differently.

Session 7: The Global Revolution

What was the legacy of the American Revolution and how did Americans who lived through it remember and interpret the event? New scholarship by Mathew Rainbow Hale, Kariann Yokota, and Dane Morrision seeks answers to these questions.

Mathew Rainbow Hale compares the American Revolution with the French Revolution to measure the revolutionary nature of the former. He argues that this comparison allows historians to better understand the contours and parameters of the impact of the American Revolution. Hale’s initial findings suggest that historians of the American Revolution need to reevaluate how they use and view the ideas of democracy and equality. Hale asserts that the French Revolution and its events shaped the way Americans viewed their revolution and its mission to bring forth democracy and equality.

Kariann Yokota would like scholars to consider how early Americans’ interactions and activities in the Pacific Ocean shaped the development of the British North American colonies and fledgling United States. Yokota observes that as Americans sought independence, Europeans sought to expand their involvement in the Pacific. After the War for Independence, Americans followed the Europeans’ lead and ventured into the region as an opportunity to assist with the growth of their new nation and to demonste their new found freedom. Yokota has found that American activies in the Pacific contributed to the economic, political, and cultural development of the United States.

Kariann Yokota would like scholars to consider how early Americans’ interactions and activities in the Pacific Ocean shaped the development of the British North American colonies and fledgling United States. Yokota observes that as Americans sought independence, Europeans sought to expand their involvement in the Pacific. After the War for Independence, Americans followed the Europeans’ lead and ventured into the region as an opportunity to assist with the growth of their new nation and to demonste their new found freedom. Yokota has found that American activies in the Pacific contributed to the economic, political, and cultural development of the United States.

Dane Morrison’s work also focuses on Americans in the Pacific. Morrison would like to know how the first generation of American traders in the Pacific viewed their American identity and how their interactions with different Pacific Rim peoples affected their portrayal of the American Revolution and its ideas. Morrison seeks answers in the Indies trade literature that emerged during the early republic period, a literature that reflects that early Americans viewed their initial forays into the Pacific as an extension of the American Revolution.

Eliga Gould commented that Hale, Yokota, and Morrison's work reveal how situating the American Revolution into global history can offer insight into the Revolution and how its ideas spread and took shape both during and after the War for Independence. Hale’s investigation reminds us that the French served as the midwives of American democracy. Morrison’s study demonstrates that Americans sought recognition as Americans and when Europeans failed to provide the desired recognition, they traveled to China to get it. Finally, Yokota’s research reminds historians that the United States began thinking about transcontinental concerns only after Americans ventured into the Pacific.

Keynotes

Woody Holton and Brendan McConville offered the two keynote addresses of the conference. Both scholars used their opportunity to lament how study of the American Revolution has waned over the last 25 years.

Holton asserted that historians of the American Revolution are suffering from an “originality crisis.” For the last 10-25 years, historians have created new work on the American Revolution by taking old ideas, adding the theories set forth by their favorite theorist (Foucault/Bourdieu/Habermas), and calling it "new work." According to Holton, applying theory to old ideas does not create new ideas or new work. Instead, it generates jargon-filled scholarship that people can’t read.

Holton offered three ideas for where scholars of the American Revolution might find new topics: The influence of ordinary people on extraordinary events, micro-comparisons, and statistical studies.

Holton offered three ideas for where scholars of the American Revolution might find new topics: The influence of ordinary people on extraordinary events, micro-comparisons, and statistical studies.

Holton posited that historians would need time to accomplish this work and overcome their “originality crisis.” Time to create “tedious" databases that will yield fascinating insight into the American Revolution. Time to learn Mandarin so we can learn how eighteenth-century Chinese people viewed Americans and their Revolution. Time to produce well thought out, quality studies.

Holton advised the audience to create time by doing away with “quickie dissertations” and by attending fewer conferences.

Brendan McConville agreed with Holton’s sentiment of an “originality crisis.” His talk began with a brief overview of how we came to this crisis: over the last 25 years scholarship has shifted the discussion away from the American Revolution and toward a study of revolutionary America and the failed promises of the Revolution.

Unlike Holton, McConville did not offer any suggestions for how scholars might find new opportunities and ideas as they return their focus to the American Revolution and War for Independence.

Do We Have an Originality Crisis?

Although Holton and McConville offered dire views for the field and its originality, the conference papers suggest historians should be optimistic.

The proffered papers reflect that historians still have a deep interest in the American Revolution and that they want to better understand it by revisiting and reexamining long-neglected events and by situating the Revolution in a global context.

I agree with McConville’s sentiment that historians need to better define what we mean by the American Revolution. Do we mean revolutionary America or the American Revolution, the event? Personally, I believe the Revolution as an event took place between 1763 and 1797 (the end of Washington’s presidency).

I agree with McConville’s sentiment that historians need to better define what we mean by the American Revolution. Do we mean revolutionary America or the American Revolution, the event? Personally, I believe the Revolution as an event took place between 1763 and 1797 (the end of Washington’s presidency).

Although I would like to see us better define and articulate what we mean by the American Revolution, it would be unwise for historians to disconnect the event from its context. History is often as much about continuity as is it is about change. In fact, understanding the continuities in an event such as the American Revolution will help us better understand the change the event offered and brought forth.

I think the best studies of the American Revolution will be those that focus on the event while placing it within its context; studies that discuss the event while also showing what preceded and succeeded it. The challenge will be fighting the urge to portray the American Revolution and independence as inevitable. We must show that contingency existed and that the events of the Revolution and its War for Independence could have turned out differently.

I left “So Sudden an Alteration” feeling optimistic and energized about the field and my scholarship. I do not see a crisis, but then again I believe that each generation has something new to say about the past.

No matter how hard we try to study the past on its own terms the present day will always creep in. The present almost always informs our scholarly interests and lines of inquiry.

Scholars who witnessed the social revolutions of the 1960s and 1970s have and still offer wonderful work about the social upheaval that took place during the American Revolution and about how the promises of the Revolution failed to include women, African-American slaves, and the poor—groups that worked to gain inclusion during the 1960s and 1970s.

My fascination with regionalism and American identity stem from the fact that I have witnessed a growing polarization in the politics of the United States. This polarization has occurred as much along regional lines as ideological ones.

Furthermore, I am not sure if historians can ever really enter into an “originality crisis.” The present always offers us new lines of inquiry. The papers offered at the conference clearly demonstrate this point even if the keynote speakers disagree.

What Do You Think?

What Do You Think?

What do you think about the future of the study of the American Revolution?

Do you think the field suffers from an originality crisis?

*Joe Adelman and Michael Hattem have also posted their impressions of this conference.