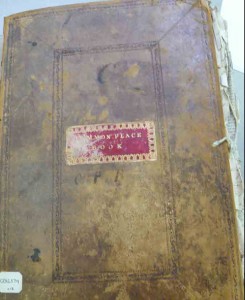

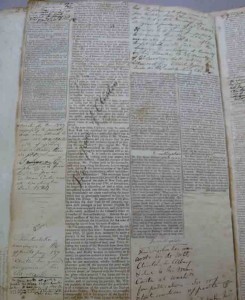

On Thursdays I volunteer in the Library at the Albany Institute of History and Art. My long-term project involves creating a finding aid for a collection that connects merchants in Albany, New York with traders in St. Croix. I am a quarter of the way through the collection and thus far I have found a lot of useful information for my book revision and material for a conference paper. Many of the documents deal with the firm Cuyler, Gansevoort & Co.--a partnership between Jacob Cuyler and Leonard Gansevoort. Within months of Great Britain and the United States ratifying the Treaty of Paris, Cuyler & Gansevoort set to work solidifying their old trade relationships and using those connections to create new ones.

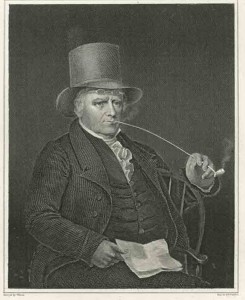

On Thursdays I volunteer in the Library at the Albany Institute of History and Art. My long-term project involves creating a finding aid for a collection that connects merchants in Albany, New York with traders in St. Croix. I am a quarter of the way through the collection and thus far I have found a lot of useful information for my book revision and material for a conference paper. Many of the documents deal with the firm Cuyler, Gansevoort & Co.--a partnership between Jacob Cuyler and Leonard Gansevoort. Within months of Great Britain and the United States ratifying the Treaty of Paris, Cuyler & Gansevoort set to work solidifying their old trade relationships and using those connections to create new ones.

Through Nicholas Hoffman of New York City, Cuyler & Gansevoort made acquaintance with "Jan Bronkhorst Merchant at Croisie in Brittany." The Albany firm sought French goods from Bronkhorst and an introduction to his partners in Amsterdam "[we] Being destitute of a Connection in Holland." Through John Murray of New York City and James Ellice of Schenectady, Cuyler & Gansevoort sought introductions to those merchants' London-based trading houses; they had met with an "unexpected disappointment" with the house of Henry Cruger & Co. at Bristol. Cuyler & Gansevoort also reached beyond New York City and formed business relationships with merchants from Boston and Philadelphia.

A contract with Captain Thomas Hook illuminates the amount of cooperation between mercantile firms based in Albany. On November 16, 1785, Cuyler, Gansevoort & Co. contracted with Hook to sail the sloop Sally to the West Indies and trade its cargo. Cuyler & Gansevoort owned one half of the cargo and one half of the Sally. The other half of the Sally and its cargo belonged to the Albany firm Stevenson, Douw & Ten Eyck. Ownership of a sailing vessel allowed merchants the freedom to send cargoes to destinations of their choice as well as limit the amount of profit they had to share with middlemen. However, sea trade could be dangerous. Bad weather could damage ships and cargoes, pirates or foreign navies could impress ships, crews, and cargoes, and spoiled cargoes or an unanticipated decline in market prices could greatly decrease the merchants' profit. Partial ownership allowed merchants to trade for maximum profit and spread out the risk. Moreover, dividing the risk made sense because it allowed merchants to put their "eggs" in more than one basket. By owning a share in a vessel and cargo, small firms like Cuyler, Gansevoort & Co. could afford to trade in multiple markets at the same time.

Although the documents within the St. Croix Collection specifically discuss people and events in early Republic Albany, they really describe people and events throughout the Early Republic United States. From this collection I have gleaned valuable information about early American trade patterns, women's involvement in trade, the shipbuilding business, the ways in which merchants used trade to reaffirm and promote their self-understandings as United States citizens, and (unrelated to trade) about Federalist electioneering practices. I plan to address these topics in more detail as I continue to work with this collection.