I do not consider myself to be a "theory-driven" historian. Theory influences the way I read and think about primary and secondary sources, but I don’t write about how specific theories apply to my argument. Or so I thought.

New Netherland Emerging Scholars Roundtable

New Netherland Emerging Scholars Roundtable

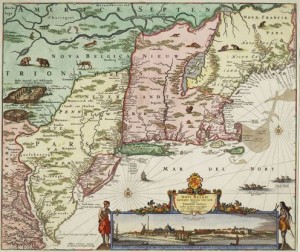

On Friday October 5, I attended the inaugural New Netherland Emerging Scholars Roundtable. Sponsored by the Dutch Consulate, the Nederlandse Taalunie, and the New Netherland Institute, the Roundtable convened for a full day of discussion about the scholarship on New Netherland by “emerging” scholars.

Eight emerging scholars and eight established scholars participated. The work of the emerging scholars explored the history of New Netherland from the vantage points of architecture, art, objects, ideas, culture, and trade. As the last presenter, I collected nearly 7 pages of notes about the history of New Netherland before the Roundtable turned its attention to my project.

I participated in the Roundtable with the hope that the other scholars would assist me with sources and ideas for how I could study the influence of Native Americans and non-Dutch Europeans on the development of the New World Dutch identity that developed in Beverwyck/Albany between 1614 and 1664. Although I began with this request, conversation quickly turned to my use of "identity" as a theoretical concept.

Roundtable Discussion

Initially, the Roundtable seemed to support my ideas about identity. Participants asked questions about how the concept worked in the 17th century, whether I had looked at religion as a major influence in identity creation, or if I had studied the contribution of African slaves to the New World Dutch Identity of Beverwyck. As I considered these questions, Walter Prevenier raised his hand: “I don’t get identity.”

I explained that I understood identity to be the way a person understood their relationship with their ethnicity, religion, community, region, and nation. I also explained that the word “identity” was fraught with ambiguity, which is why I avoid using the word in my written work as much as possible. Instead, I use “self-understandings” or refer to specific subjects of my study.

Prevenier pressed further: “How can you tell how the Dutch colonists identified unless they tell you in the written record ‘I identify as Dutch’?”

Great point.

Without intending to, I had latched on to "identity" as a theory and centered the argument of my dissertation on it. Subconsciously I knew I stood on shaky ground, but the urge to make a grand argument that would contribute to the historiography overwhelmed my objections.

REVELATION

REVELATION

Historical arguments do not have to be steeped in theory to be interesting or compelling.

Prevenier’s point seemed obvious. In fact, as soon as he articulated it, I understood his confusion and realized that it mirrored my own, hence why I used the terms “identity” and “self-understandings” sparingly in my written work.

Prevnier’s remarks helped me to admit that I was trying to force a modern-day concept (albeit a popular one) on my historic subjects who would not have understood “identity” the way I do.

Once I stated this realization out loud, I felt free to leave the theory of “identity” behind me.

Book Proposal Tweaks

The Roundtable scholars supported my decision to abandon "identity." No one advocated a complete overhaul of my project. Instead we discussed different ways I could reframe the argument I want to make, which is something along the lines of "early Americans used cultural adaptation as a mechanism for surviving life in a sparsely-settled frontier, war, intercultural diplomacy, politics, and economic and demographic change."

I am still working on my new 1-2 sentence explanation of my project, but once I have it, I will tweak my book proposal to reflect it.

I am grateful for the New Netherland Emerging Scholars Roundtable participants for their conversation and ideas. They provided me with invaluable insight that will improve my book.

What Do You Think?

What do you think about using theory to make a historical argument? Do you think theory is necessary to answer our questions about the past? Do you think historians overuse theory?