Kilmainham Gaol stands as an important building in modern Irish History.

Since 1796, the Gaol has served as the home of many political prisoners, including 13 of the 16 leaders of the pivotal Easter Rising in 1916.

Kilmainham Gaol stands as an important building in modern Irish History.

Since 1796, the Gaol has served as the home of many political prisoners, including 13 of the 16 leaders of the pivotal Easter Rising in 1916.

Brief History of Kilmainham Gaol

Kilmainham Gaol opened in 1796 as the County Gaol for Dublin.

The Gaol received the name "Kilmainham" as the British built it in the Kilmainham district of Dublin.

When it opened, Kilmainham was the most modern prison in Ireland.

British reformers designed the original west wing of the prison with a number of cells, each designed to house one prisoner. Previous to Kilmainham Gaol, prisoners intermingled with one another and suffered the arbitrary punishment of the gaol keeper.

British reformers designed the original west wing of the prison with a number of cells, each designed to house one prisoner. Previous to Kilmainham Gaol, prisoners intermingled with one another and suffered the arbitrary punishment of the gaol keeper.

This meant that debtors intermingled with murderers, petty thieves, and disturbers of the peace and that those with some resources were able to pay the gaoler for better food and treatment.

The British prison reformers designed Kilmainham to be different.

The reformers removed the arbitrary punishment of the gaoler by treating prisoners with like crimes equally. Prisoners did not intermingle except during their exercise period.

The original prison contained no windows.

Late-18th century prisoner reformers thought that the cool air helped the process of reflection.

Unfortunately for the inmates, Kilmainham has limestone walls, which absorb moisture. The moisture in the walls combined with the cool air to make Kilmainham an unpleasant place.

The Potato Famine & Kilmainham

The unpleasantness of the place increased during the great potato famine (1845-1850).

The potato blight rendered most Irish tenant farmers unable to pay their rents or feed their families. Many of these farmers moved into Irish cities or abroad seeking opportunities.

The potato blight rendered most Irish tenant farmers unable to pay their rents or feed their families. Many of these farmers moved into Irish cities or abroad seeking opportunities.

Disgusted with the number of beggars and vagrants clogging Dublin’s streets, the Irish Parliament passed an anti-vagrancy law. Anyone caught in the streets begging was sent to jail.

The influx of vagrants overfilled Kilmainham Gaol. As many as 5 or 6 prisoners occupied cells that had been designed for 1.

The commandant of Kilmainham cut food rations to 1 meal of bread and water or milk per person, per day. Even with this knowledge, many starving farmers and their families resorted to begging in Dublin’s streets with the hope that they would be thrown in Kilmainham. 1 meal a day was better than none.

Victorian Addition

In 1861, the British built a second wing for the prison.

In 1861, the British built a second wing for the prison.

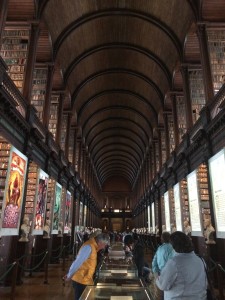

The newer Victorian wing consists of 96 cells.

Like the original wing, the prison’s architects designed the new wing to house 1 prisoner per cell and the guards enforced silence.

A large glass ceiling draws your eyes toward the heavens. These windows allow a lot of sunlight to pour into the wing.

Victorian prison reformers believed that silence, sunlight (a reminder of God), and solitude would encourage the prisoners to reflect on their deeds and reform.

For those resistant to reform, the Victorians supplied periods of hard labor in the stone breaking yard to break the inmates’ physical and mental will.

Political Prisoners

Kilmainham has a long history of housing political prisoners, mostly Irish nationalists who fought for Irish independence from Great Britain.

Kilmainham has a long history of housing political prisoners, mostly Irish nationalists who fought for Irish independence from Great Britain.

Henry Joy McCracken holds the distinction of being the first political prisoner in Kilmainham. He first entered the prison in 1796.

McCracken founded the United Irishmen, an organization devoted to Irish independence.

McCracken reentered the prison in 1798. The British executed him by hanging for his role in the rebellion of 1798.

Inspired by the French Revolution and by the words of Thomas Paine, the United Irishmen led an unsuccessful attack upon the British in an attempt for Irish independence.

The most famous political prisoners held in the prison took part in the 1916 Easter Rising.

1916 Rising

On April 24, 1916, Easter Monday, between 1,500 and 2,000 nationalists seized control of the General Post Office (GPO) and surrounding area on present-day O’Connell Street.

On April 24, 1916, Easter Monday, between 1,500 and 2,000 nationalists seized control of the General Post Office (GPO) and surrounding area on present-day O’Connell Street.

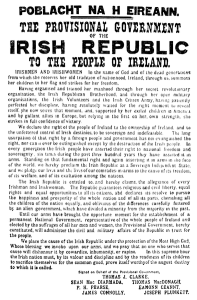

From the GPO, Patrick Pearse read the Proclamation of the Republic, the Irish equivalent of the United States’ Declaration of Independence.

The Rising lasted 4 days before the 5,000-man British Army subdued it.

The British Army counted 116 dead, 398 wounded.

The civilians and nationalists had more casualties: 318 dead, 2,217 wounded.

In addition, the GPO and much of present-day O’Connell Street had been destroyed as a result of fire and British artillery shells.

The British Army arrested 14 of the Rising’s leaders.

They sent 13 to Kilmainham Gaol and 1 to Dublin Castle for medical treatment.

They sent 13 to Kilmainham Gaol and 1 to Dublin Castle for medical treatment.

Between 3rd and 12th May, 1916, the British Army executed by firing squad the 14 leaders they had arrested.

Unable to stand up for his execution, the Army tied James Connolly, the wounded leader, to a chair before they shot him.

The stories of the individual men and their executions helped to make this unpopular rising a popular one for many Irish men and women.

Irish history scholars attribute the start of the Irish War for Independence (1919-1921) to the execution of these leaders.

Conclusion

Kilmainham Gaol is a must see.

This 1 hour, guided tour will teach you about prisons and prison life between the late 18th and early 20th centuries.

It will also provide you with a lot of information about Ireland’s various independence movements.

What Do You Think?

What Do You Think?

What is the most interesting place you have visited?