On September 13, 2014, Tim and I embarked on a week-long cruise of coastal Canada.

Our ports of call included Halifax, Nova Scotia, Sydney, Nova Scotia, Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, Québec City, Québec, and Montréal, Québec.

On September 13, 2014, Tim and I embarked on a week-long cruise of coastal Canada.

Our ports of call included Halifax, Nova Scotia, Sydney, Nova Scotia, Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, Québec City, Québec, and Montréal, Québec.

Tim called this trip our vacation; I called it our “French and Indian War Tour.”

In this post you will find information about the sites I saw during my “French and Indian War Tour.”

Tip: Did you know that you can make my photos larger by clicking on them?

Halifax, Nova Scotia

I had to make tough choices about the history sites and museums I wanted to visit during out 8.5 hours in Halifax.

In the end, I chose a full-day trip to Grand Pré and a Nova Scotia winery in the Annapolis Valley.

Located along the Bay of Fundy’s Minas Basin, Grand Pré stands as a UNESCO World Heritage Site that memorializes the Expulsion of the Acadians by the British between 1755 and 1764.

Acadians are descended from French colonists who settled in Nova Scotia during the 1680s.

Acadians are descended from French colonists who settled in Nova Scotia during the 1680s.

Many of the colonists established farms on the rich alluvial soils along the Bay of Fundy. The farmers constructed a system of dykes and wooden sluices to drain and protect their land from the Bay’s extreme tidal range of 40-60 feet.

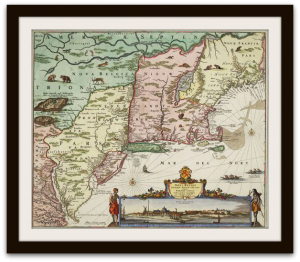

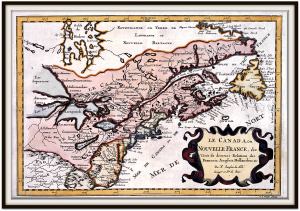

Both Great Britain and France claimed sovereignty over Nova Scotia. As a result, imperial warfare caused the island to change hands several times between 1700 and 1755. Each war ended with Great Britain returning the island to France, until the French and Indian War; the Treaty of Paris 1763 ended the war and awarded Nova Scotia to the Great Britain.

Neither the French nor the British trusted the Acadians. During each war, the farmers declared neutrality. In theory, they refused to supply either army with supplies, weapons, or men. In practice, both the French and British armies extracted assistance from the Acadians by threatening their families and property holdings.

In 1755, the British officers worried that the Acadians would reverse their hard-won victory over the French Army. They feared that the Acadians would invite French soldiers to attack them and assist the French effort.

The British military lessened its fears by expelling the Acadians from Nova Scotia.

The Grand Pré World Heritage Site tells the story of the British Expulsion of the Acadians (1755-1764). Exhibit placards and a multimedia show present information about the Acadian diaspora from both Acadian and British points of view. An exhibit in the visitor center also depicts how the Acadians drained and protected their land with dykes and wooden sluices using sizable models.

Sydney, Nova Scotia

Our stop in Sydney afforded Tim and I the opportunity to visit the most contested site in colonial North America: Fortress Louisbourg.

The Treaty of Utrecht (1713) ended Queen Anne’s War (1702-1713), but its articles did little to assuage French fears that the British might seize all of their possessions in North America. The articles awarded Great Britain all North American lands along the Atlantic seaboard with the exception of Île Royale (Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia).

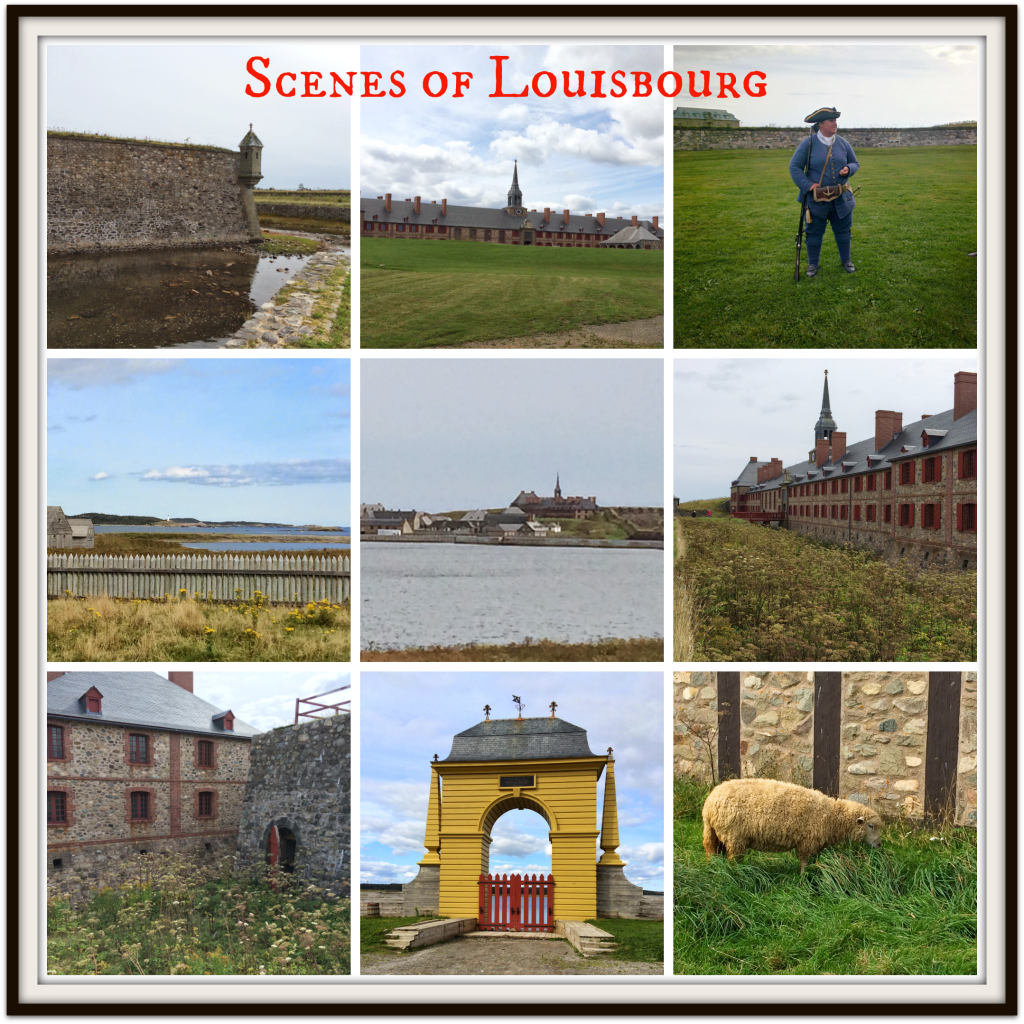

The French sought to strengthen its hold of Île Royale. Between 1720 and 1740 they built a large fortress near a prosperous fishing village on the northeastern tip of the island. The French called the fortress and the settlement around it Louisbourg and they protected both with a massive stone wall.

The French sought to strengthen its hold of Île Royale. Between 1720 and 1740 they built a large fortress near a prosperous fishing village on the northeastern tip of the island. The French called the fortress and the settlement around it Louisbourg and they protected both with a massive stone wall.

New Englanders despised the French presence in New France. Not only were the French predominately Catholic, but between 1689 and 1713, French soldiers and Native Americans raided frontier settlements in the region. The Yankees feared that the French would use Louisbourg as an additional base from which to attack them.

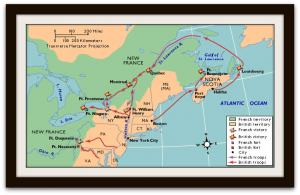

In 1745, New Englanders seized the opportunity afforded by King George’s War (1744-1748) to attack Louisbourg. Against the odds, the Yankees captured the fortress and its town. However, their possession proved short-lived. In 1748 the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle ceded Louisbourg back to the French.

The French and Indian War rekindled British desires to reacquire Louisbourg. In 1758, a large British force laid siege to the fortress and town.

The French surrendered after 6 weeks of daily bombardment.

The 1758 surrender of Louisbourg brought forth the predictions the French government had made in 1713: the British used the fortress as a launching point for its Siege of Québec in 1759.

In 1760, the British did not know that the Treaty of Paris 1763 would uphold their possession of Île Royale. In an effort to prevent the French from retaking Louisbourg, the British blew up the fortress, town, and the thick stone walls that protected them.

The fortress and town that stand at Louisbourg today are exact reproductions of the original fortress and town buildings.

In 1960, the Canadian government commenced a project to rebuild the Fortress, some of its walls, and 1/5th of the buildings that stood within the town.

Today, Parks Canada operates Louisbourg as a living history museum. In most buildings and areas throughout Louisbourg you will find men and women dressed as 18th-century French soldiers and townsfolk. These interpreters interact with you and explain how the French colonists and soldiers lived and work.

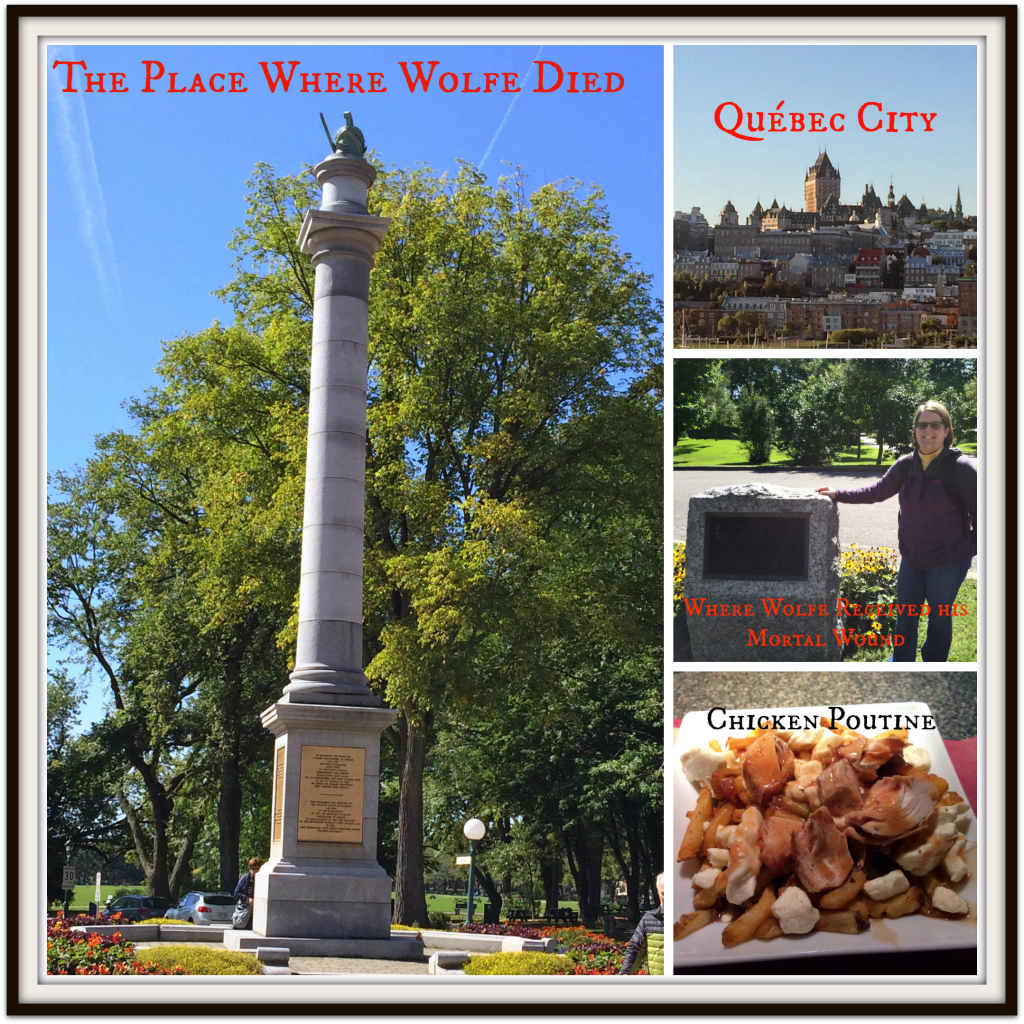

Québec City, Québec

Our French and Indian War Tour ended on the Plains of Abraham, located in Québec City.

Established in 1608 by Samuel de Champlain, Québec City stands as one of the oldest European settlements in North America.

In 1985, UNESCO declared the Historic District of Old Québec to be a World Heritage Site in an effort to protect the remains of the stone walls that once protected the city.

In 1985, UNESCO declared the Historic District of Old Québec to be a World Heritage Site in an effort to protect the remains of the stone walls that once protected the city.

The Plains of Abraham lie just outside of these walls.

The 1759 British Siege of Québec climaxed with a Battle on the Plains of Abraham.

The battle took place on September 13, 1759 and lasted about 30 minutes.

General James Wolfe and his 4,800-man British army fought General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm and his 2,000-man French army. Both generals fought on the field and both received mortal wounds.

Wolfe’s army won.

The British victory did not end the French and Indian War, but it ended the British quest for dominance in North America.

Wolfe’s victory brought New France under British control, a fact which the Treaty of Paris 1763 confirmed and maintained.

In the early 1900s, the Canadian government established the Plains of Abraham as its first national park. Today, Parks Canada administers this grand park, which provides Québec’s urban populace with museums, gardens, and outdoor recreational space.

Monuments and memorials recounting and commemorating events that took place during the 1759 battle dot the landscape.

Tim and I spent several hours walking through the park. We found where Wolfe received his mortal wound and the monument that commemorates the place where he died. We also walked along the cliffside boardwalk.

Peering over Québec's cliffs gave me a new appreciation for the efforts Wolfe and his men exerted when they scaled them 255 years ago.

Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island

In between our stops in Sydney and Québec City, our ship docked at Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island.

In addition to taking a scenic drive and visiting the Anne of Green Gables House, Tim and I walked around Charlottetown where we found Province House, the birthplace of the Confederation of Canada.

In 1864, the political leaders of Prince Edward Island invited representatives from Canada’s maritime provinces to Charlottetown to discuss forming a confederation of the Canadian maritime provinces. Representatives from the mainland heard about this meeting and invited themselves to it.

In 1864, the political leaders of Prince Edward Island invited representatives from Canada’s maritime provinces to Charlottetown to discuss forming a confederation of the Canadian maritime provinces. Representatives from the mainland heard about this meeting and invited themselves to it.

In September 1864, twenty-three political leaders from Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario, and Québec gathered in Charlottetown to discuss what forming a confederated and united Canadian government might look like and mean for the British colonies.

Three years later, on July 1, 1867, Parliament passed the British North America Act. Queen Victoria signed the act and the Dominion of Canada was born.

I had no idea that my visit to Prince Edward Island would lead me to the birthplace of Canadian Confederation. Although the Province House did not fit within my French and Indian War-themed tour, it provided a nice epilogue to it.

The Province House museum and site tells the story of how Canada evolved from a group of British colonies to a united, independent nation.

Conclusion

Tim and I enjoyed our cruise through coastal Canada and down the St. Lawrence River. Our brief 6-8 hour stops in Nova Scotia, PEI, and Québec introduced us to the history and natural beauty of these provinces. Some day we hope to return and spend more time exploring them.

Share Your Story

What was the last historic site you visited?