What tools do you use to take notes at conferences?

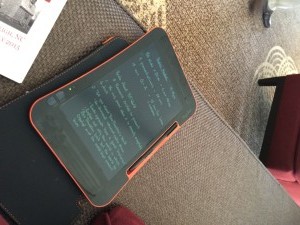

You may recall that I am a huge fan of Boogie Board Sync, an eWriter that has the tactile feel of pen and paper and saves directly to Evernote. Over the last month, I have taken my Boogie Board to two conferences with the hope that I had stumbled upon the perfect conference note taking tool.

In this post, I share my experiences using my Boogie Board Sync at professional conferences and why I think the eWriter is an extremely useful tool for historians.

The Search for the Perfect Conference Note Taking Surface

Legal Pads

Have you ever gone to a conference and tried to take notes on a legal pad?

Legal pads and pens served as my first conference note taking tools. They seemed like the perfect choice: dark ink and a paper pad that doubled as a sturdy writing surface. However, by the end of my first conference these note taking implements had let me down.

Legal pads involve noisy page turns. Its writing surface becomes flimsy the closer you get to the end of the pad.

Frustrated, I took a [simpleazon-link asin="8883701127" locale="us"]Moleskine classic notebook[/simpleazon-link] to my second conference.

Sturdy Notebooks

Moleskine notebooks provide a sturdier writing surface than a legal pad, but they can be difficult to keep flat as you write.

Moleskine notebooks provide a sturdier writing surface than a legal pad, but they can be difficult to keep flat as you write.

Every time I approached the middle of the notebook the binding caved in and changed the angle of my writing surface. As a person who maintains their focus and processes information best when writing, I take a lot of notes and I take them fast. The frequent change in writing angle annoyed me as it slowed my ability to jot down notes quickly.

Despite this flaw, and the fact that I had to replace my notebook every fourth conference, I continued to take notes in a Moleskine until two or three years ago, when it became socially acceptable to use laptops at conferences.

Laptops

Taking notes with my laptop has made my life easier. As I type faster than I hand write notes, my laptop allows me to capture more information. It also has the advantage of providing me with a sturdy writing surface with endless amounts of virtual paper.

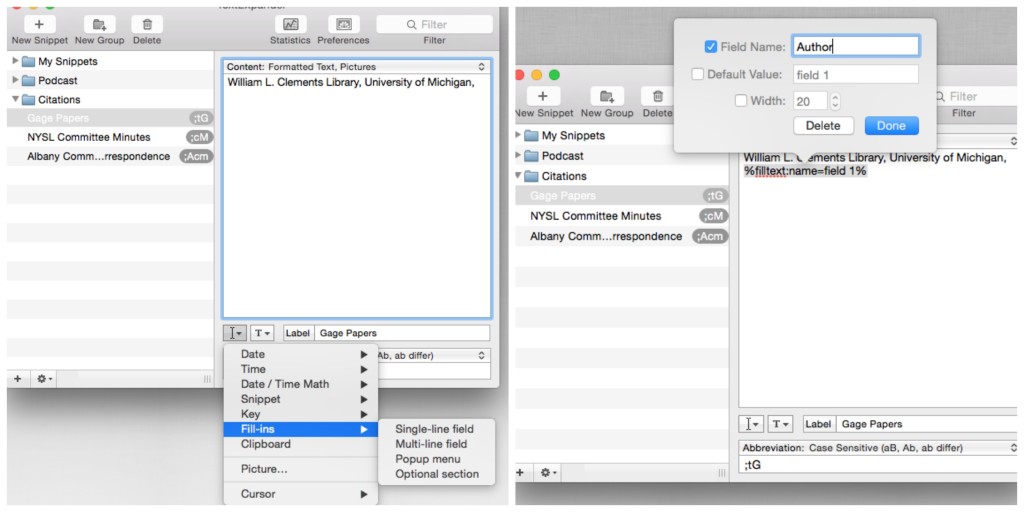

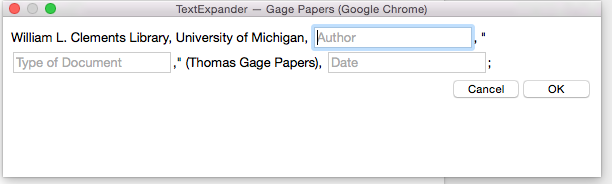

Taking notes with my laptop has also ensured that I remember and find my notes when I need them.

I type my notes into Evernote, my digital filing cabinet. Every time I perform a keyword search, Evernote pulls up relevant information that I have stored in the app. This information includes notes I have taken at conferences.

With that said, recording notes on my laptop has not been a perfect solution. Although my Macbook Air has a quiet keyboard, those who sit next to me hear the soft clicking of keyboard keys as I type.

Additionally, I have short arms. I often place my backpack on my lap and prop my laptop on top of my backpack in order to type comfortably. This tower of stuff provides a comfortable typing angle, but often means a slight shift in leg position can turn my writing surface into a wobbly mess.

Boogie Board Sync

In June and July, I tried taking conference notes on my Boogie Board Sync.

Like my laptop, my Boogie Board never runs out of paper and it can save my notes directly to Evernote. Unlike my laptop there is no audible clicking of the keys and the writing surface is wide enough that I can comfortably take notes with the surface resting on my lap or knee should I cross my legs.

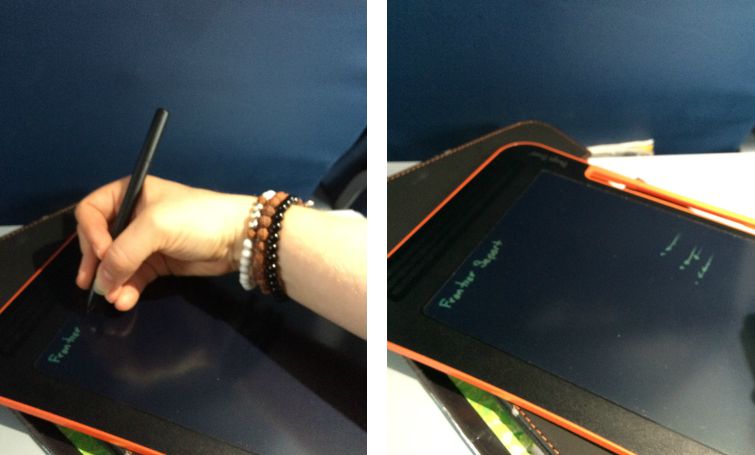

However, like my other note-taking tools, Boogie Board has its drawbacks. First, you may mark the writing surface if you wear a watch or bracelet below your writing hand. The marks will erase when you press the “erase” button, but sometimes the marks can interfere with the clarity of your notes when you sync them to Evernote.

Second, Boogie Board does not assist with tweeting.

When I type notes into my laptop that seem tweetable, I cut and paste the information into my Twitter app and tweet them.

When I take tweetable notes on my Boogie Board, I have to snap the stylus back into the Boogie Board, pull out my smartphone, and type the information I want to tweet into my Twitter app.

The extra steps that tweeting from Boogie Board requires means I might miss important information if I live tweet a panel. Therefore, when I take notes with my Boogie Board, I often wait until a break in the Q & A, or until after the panel, to tweet.

Conclusion

Until I find a “Goldilocks” note taking tool, I will alternate between my laptop and [simpleazon-link asin="B00E8CIGCA" locale="us"]Boogie Board[/simpleazon-link].

I will use my laptop when I want to live tweet a panel. I will use my Boogie Board when a room lacks WiFi, good cell signal, or I want to attend a panel without tweeting.

I will also carry my Boogie Board to every conference I attend, even if I plan on using my laptop. Boogie Board's long battery life ensures that if my laptop runs out of power, I won’t be without a great note taking device.

Share Your Story

What is your preferred conference note taking method?