What would have happened if the Constitution of the United States had not had its Three-Fifths clause?

Joe Adelman poses this thought-provoking question in “Alternative Fractions,” a post that responds to both Rebecca Onion’s “What if?” essay on Aeon and Kevin Gannon’s “The Constitution, Slavery, and the Problem of Agency."

What would have happened if the Constitution of the United States had not had its Three-Fifths clause?

Joe Adelman poses this thought-provoking question in “Alternative Fractions,” a post that responds to both Rebecca Onion’s “What if?” essay on Aeon and Kevin Gannon’s “The Constitution, Slavery, and the Problem of Agency."

I love counterfactuals because they make me think about contingency. However, the counterfactual posed by Joe requires serious thought because of its scope.

In this post, I take a stab at addressing what would have happened if the Three-Fifths clause had not been added to the United States Constitution.

A Brief Overview of the Three-Fifths Clause

The Three-Fifths clause appears in Article I, Section 2 of the United States Constitution.

Article 1, Section 2 outlines the House of Representatives. It addresses who can serve as a Representative and how population will determine House membership.

Here is the Three-Fifths clause:

“Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons."

The clause represents a compromise. The Articles of Confederation apportioned taxes according to land values. States undervalued their land to lower their tax burden. During the Constitutional Convention (1787) many delegates wanted population to be the basis for tax allocation.

As the Convention debated the merits of the “Connecticut Plan,” the version of the Constitution that supported a bicameral legislative branch, northern states and southern states disagreed over how slaves would count if the Constitution based representation in the House of Representatives on population. James Wilson of Pennsylvania and Roger Sherman of Connecticut proposed a compromise to entice southern support for the population-based House: Each slave would count as three-fifths of a white person.

The result of this compromise: The delegates agreed on the Constitution and southern representation in the new government increased from about 38 percent under the Articles of Confederation government to about 45 percent under the new Constitution. This increase in representation gave southerners the power they needed to control presidential elections with electoral votes. However, the representative advantage proved short lived as the population in northern and western states grew more rapidly than in southern states.

Major Components of the Three-Fifths Clause Counterfactual

Joe's counterfactual question has two major components that if we altered their history would have far-reaching implications.

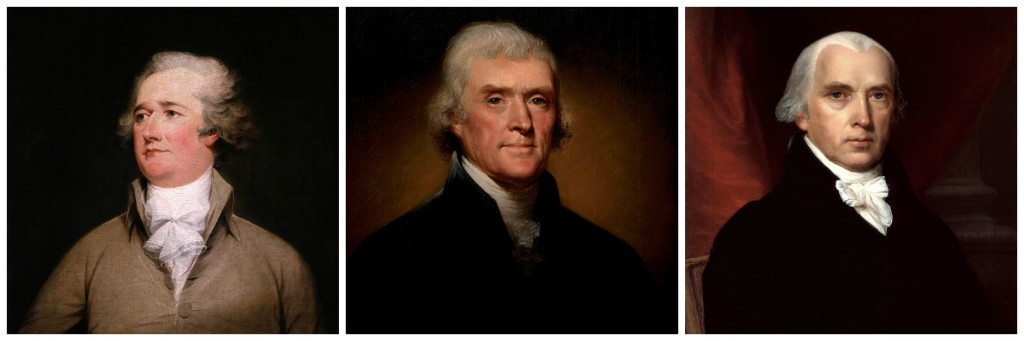

Presidential elections, 1789-1828: Five of the first seven presidents hailed from southern states; four from Virginia.

Congressional Representation: Without the Three-Fifths clause congressional leaders may not have come from the south and legislation that failed to pass without southern support would have passed.

One Brief Scenario for the Three-Fifths Clause Counterfactual

If the states had ratified the Constitution without the Three-Fifths clause the history of the nation would be very different.

Northern states would have had more control in both the House of Representatives and the Electoral College. This means George Washington may have been the only member of the “Virginia Dynasty” to serve as president between 1789 and 1825.

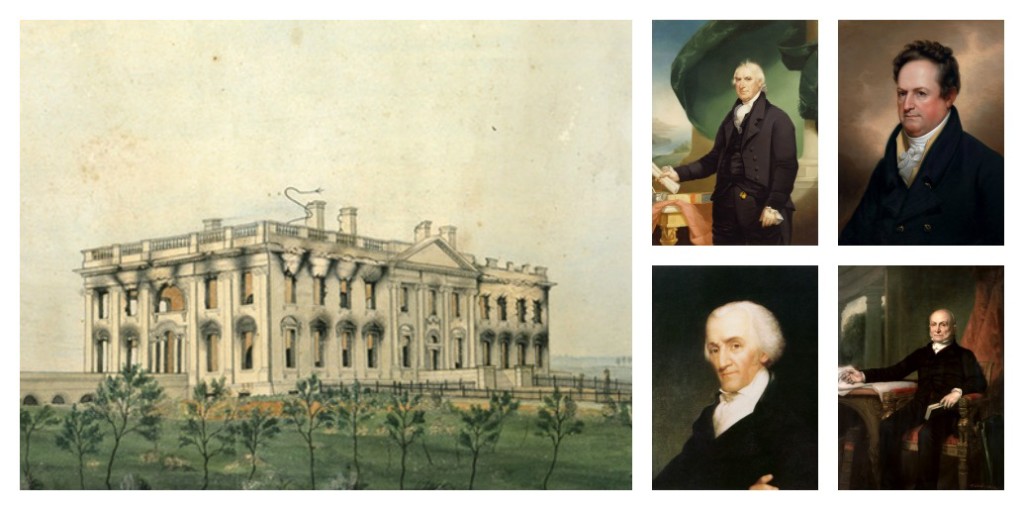

Alexander Hamilton would not have met Thomas Jefferson and James Madison “in the room where it happen[ed]” to exchange congressional votes for removing the nation's capital to the banks of the Potomac River because Hamilton would not have needed their support to get his debt assumption bill passed.

Without Hamilton, Jefferson, and Madison's backroom deal, the nation’s capital would not have moved south. It would have moved west from New York City.

Actual History

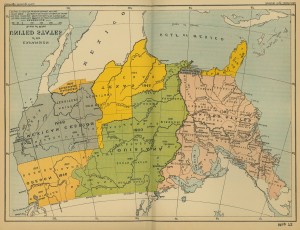

After the Revolution, 700,000 to 800,000 New Englanders migrated into New York State. The Yankees flooded into post-war New York City and established new, New English towns in northern and western parts of the state. Once the migrants filled New York they pushed west to Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, and Illinois. Americans further south also migrated. They moved into what would become Kentucky and Tennessee.

As the population expanded in the west, it also burgeoned in eastern cities like New York City and Philadelphia. The cost of living in these cities rose as demand for living space and life necessities increased. On November 1796, the New York State Assembly and Senate voted to relocate the state capital to Albany. They made this decision partly because the population of the state had grown in its northern and western regions, but mostly because New York City had become too expensive for many representatives to live in and travel to.

The economic and population factors that caused the New York State government to relocate its capital to a more central and cheaper location would have also forced the federal government to relocate from New York City. As Philadelphia experienced a similar rise in cost of living, I believe a different negotiation would have occurred and the capital of the United States would have moved to a place like Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Cincinnati, Ohio, Lexington or Louisville, Kentucky, or Indianapolis, Indiana.

A Return to Counterfactual History

Without southern control of the Electoral College, John Adams would have won the Election of 1800 handily, even amidst Jeffersonian criticism for the Alien and Sedition Acts.

Would President Adams have made the Louisiana Purchase?

Yes, presuming Napoleon’s situation in France remains on its actual historical trajectory.

The loss of the French forces in Saint Domingue in 1802/1803 and France’s wars in Europe would have have forced Napoleon to raise capital by selling Louisiana to the United States. A shrewd Yankee, Adams would have found a way to make this purchase happen. Even if Adams hadn’t been perceptive enough to see the bargain Napoleon offered, his wife Abigail would have and she would have talked her “Dearest Friend" into the purchase.

After President Adams, the United States would have had more northern presidents. Men like George Clinton, DeWitt Clinton, Rufus King and Daniel Tompkins of New York, and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts offer real possibilities. John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts also would have served and possibly before 1825.

Aspects that Require More Thought

Joe poses an intriguing counterfactual question. Without the Three-Fifths clause a lot would have been different. Even after investing some time into thinking about this counterfactual, several big questions remain unanswered in my mind:

Would the United States have declared war against Great Britain in 1812?

Would the charter of the First Bank of the United States have been extended? If so, what would that have meant for the economy of the United States? Would the Panics of 1819 and 1837 have happened?

How would a northern or western president's approval of the Bonus Bill of 1817 have changed western expansion and internal commerce?

If the north and west had secured electoral and legislative power sooner than it did, would the Compromise of 1820 have been necessary?

Would the expansion of slavery have been an issue?

Would the nation have overpowered the south and voted to gradually abolish slavery before the Civil War?

What Do You Think?

What do you think would have happened in any of the above scenarios?