It’s August and I’ve somehow found myself with 7, straight weeks at home. It’s the first time I’ve been home for a full month this year. (Hence why this blog has been a bit of a ghost town.)

Since January, I’ve been on a type of “history podcast tour.” Historians & history lovers have become fascinated with Ben Franklin’s World and its success, and they want to know more about the show, how I produce it, and the role podcasts and other digital media will play in the future of historical scholarship. As such, I’ve spoken at a lot of conferences and sat for interviews for podcasts, blogs, and radio.

It’s August and I’ve somehow found myself with 7, straight weeks at home. It’s the first time I’ve been home for a full month this year. (Hence why this blog has been a bit of a ghost town.)

Since January, I’ve been on a type of “history podcast tour.” Historians & history lovers have become fascinated with Ben Franklin’s World and its success, and they want to know more about the show, how I produce it, and the role podcasts and other digital media will play in the future of historical scholarship. As such, I’ve spoken at a lot of conferences and sat for interviews for podcasts, blogs, and radio.

I’ve participated in a lot of conversations about podcasting, historical scholarship, and the historical profession over the last 7 months. It’s been a lot of fun and these experiences have revealed several key questions people have about these topics:

1. What is the role of podcasts and other digital media in the future of historical scholarship?

2. What has the impact of Ben Franklin’s World been on furthering historians’ ideas about history?

3. How are you making a living podcasting/what are you doing with your career?

I’ve heard these questions enough that a couple of blog posts with answers seem like a good idea. In this post, I’ll answer the first two questions. In a second post, I’ll answer “how are you making a living/what are you doing with your career?”

What is the role of podcasts and other digital media in the future of historical scholarship?

When most historians ask this question, what they really want to know is: do podcasts and digital media compete with traditional books and articles?

My answer: No.

Digital media such as podcasts, blog posts, and digital videos complement traditional history books and articles. They also complement museum exhibits and historic sites.

The 21st-century is a mobile age. We live on our smartphones and time has become our most valuable resource because our ability to connect to the internet and with people anytime, anywhere has drastically multiplied the demands on our time. This doesn’t mean that people dislike reading books or visiting museums. It means they have less time (or feel like they have less time) to devote to those activities. As a result, they want to know that they are going to enjoy something and benefit from an experience before they invest time and money into having an experience.

This is where digital media complements traditional books, articles, and exhibits. High-quality, well-researched, and well-produced scholarship is still very important and the need for it is not diminishing. However, this scholarship suffers from a discoverability problem.

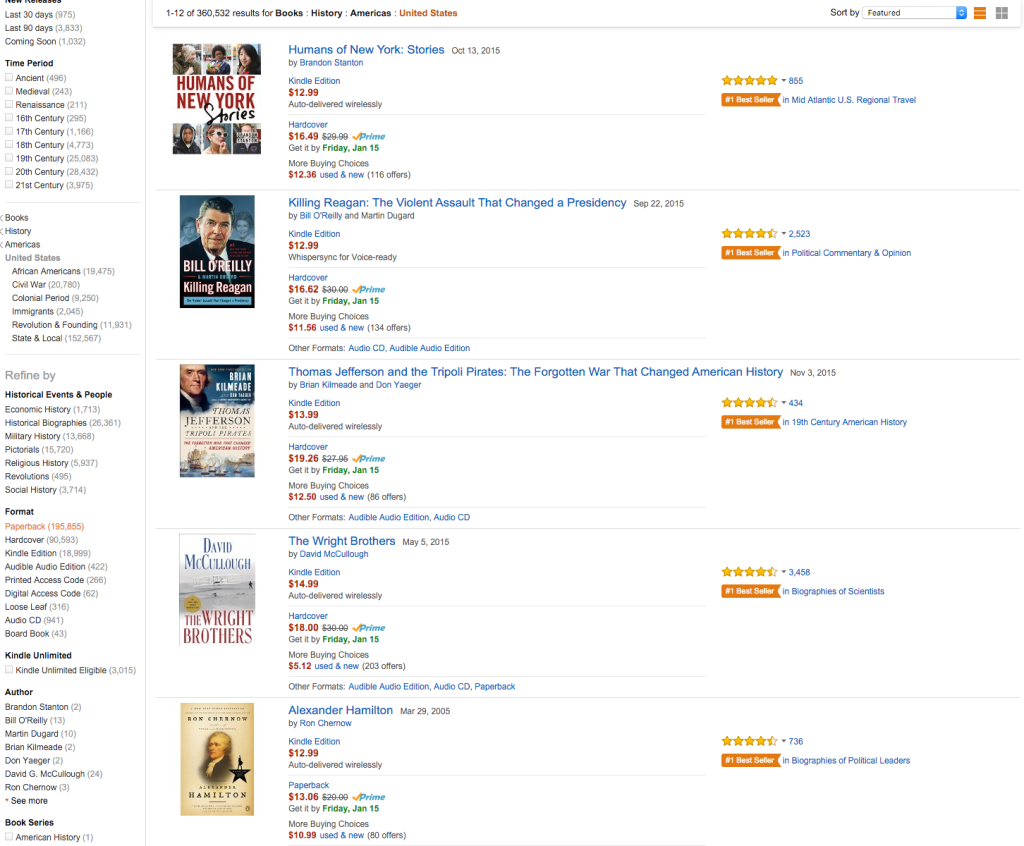

For example, Barnes & Noble doesn’t stock books from most academic publishers. They sell end cap and prime sales space to big, for-profit publishers with deep pockets. What books are those big publishers putting into those visible spaces? Usually those by “Fox News Historians” and journalists with large platforms. This means that many high-quality, fascinating history books by top-notch scholars go unstocked by bookstores and unnoticed by people who would be very interested in them, if they knew they existed.

Digital media such as blog posts, podcasts, and video create awareness. They allow potential readers to know that there are great history books and articles available and where they can find them. Digital media also provides easy and convenient ways for potential readers to get a feel for the author, the history they are conveying, and the quality and depth of the historian's research before they invest time and energy into finding a particular book, or article, and reading it.

I’ve found podcasts to be the best digital media for creating broad awareness because it’s presently the perfect digital media for our mobile age. You can listen to podcasts whenever and wherever you want to, which makes them appealing and fun fillers of commuting/exercise/dog walking/cooking/cleaning/waiting time. Plus the intimacy of the medium allows listeners to feel like they have a bond with their favorite hosts and guests.

This is why listeners repeatedly tell me that I’m costing them a fortune. They buy the history books and visit the historic sites they hear about on Ben Franklin's World because they get a great preview of what they will see, learn, and of the personalities and processes of the historians who authored the books or exhibits.

My prediction for the future: Colleges and universities will create and add digital media programs to both undergraduate and graduate curriculums in academic and public history specialties. Departments will find this profitable in the sense that faculty and student-produced media will create awareness about their programs and the work of their faculty and students and in the sense that these programs will teach students tangible, technical communications skills that companies (and corporatized colleges and universities) desire.

What has the impact of Ben Franklin’s World been on furthering historians’ ideas about history?

Statistical Measurement: Downloads have risen from 288 in October 2014 to an average of almost 69,000 per month in 2016. In a survey I conducted in late 2015, 41 percent of the Ben Franklin's World audience reported that they had purchased a book or visited a historic site as a result of the show.

Objective Measurement: I receive e-mails, tweets, and Facebook messages from listeners on a daily basis that contain questions about history, topics for future shows, and that both thank me for introducing them to a book or exhibit of great interest to them and curse me because they now spend too much money on history books. Similarly, listeners reach out to show guests too. Listeners ask guests further questions about their work and attend guest talks.

Parting Thoughts

Historians should embrace rather than fear digital media. Digital media is, and will, play a big role in keeping traditional historical scholarship alive and well and in reversing the downward trend in major and course enrollment numbers. Plus, digital media offers historians new ways to practice historical scholarship. More options breed creativity and innovation, which every profession needs if it wants to stay healthy and relevant.

On April 18, 2017, a new preview episode of the Doing History: To the Revolution! series will post on Ben Franklin's World. It will be my most creative episode yet because it tells a story and uses sound to enhance the story I'm telling. The Omohundro Institute posted a piece I wrote about thinking through how to use sound to convey history on it's blog, Uncommon Sense.

I've been thinking a lot about horses. Specifically, what a Narragansett Pacer mare would have sounded like galloping on a dirt road in mid-April in the dead of night.[1]

On April 18, 2017, a new preview episode of the Doing History: To the Revolution! series will post on Ben Franklin's World. It will be my most creative episode yet because it tells a story and uses sound to enhance the story I'm telling. The Omohundro Institute posted a piece I wrote about thinking through how to use sound to convey history on it's blog, Uncommon Sense.

I've been thinking a lot about horses. Specifically, what a Narragansett Pacer mare would have sounded like galloping on a dirt road in mid-April in the dead of night.[1]

Last week I had the opportunity to spend some time at the

Last week I had the opportunity to spend some time at the  I often wish I had some sort of time creation device. I'd take Hermione's time turner if it were available. However until such a device exists, I must create time the old fashioned way: by finding and making it within my schedule.

I need time for my new research project on the Articles of Confederation. I started this new project during a two-day research trip I tied in with a speaking engagement in late October. Since then progress on the project has been slow, but I'm making progress.

I often wish I had some sort of time creation device. I'd take Hermione's time turner if it were available. However until such a device exists, I must create time the old fashioned way: by finding and making it within my schedule.

I need time for my new research project on the Articles of Confederation. I started this new project during a two-day research trip I tied in with a speaking engagement in late October. Since then progress on the project has been slow, but I'm making progress. It’s August and I’ve somehow found myself with 7, straight weeks at home. It’s the first time I’ve been home for a full month this year. (Hence why this blog has been a bit of a ghost town.)

Since January, I’ve been on a type of “history podcast tour.” Historians & history lovers have become fascinated with

It’s August and I’ve somehow found myself with 7, straight weeks at home. It’s the first time I’ve been home for a full month this year. (Hence why this blog has been a bit of a ghost town.)

Since January, I’ve been on a type of “history podcast tour.” Historians & history lovers have become fascinated with  What makes popular history books "popular?"

Over the last few months, I have read several popular history books for

What makes popular history books "popular?"

Over the last few months, I have read several popular history books for